The News

ABUJA, Nigeria — A new price hike on petrol has frustrated Nigerian drivers grappling with scarce fuel supplies and pushed up the cost of living.

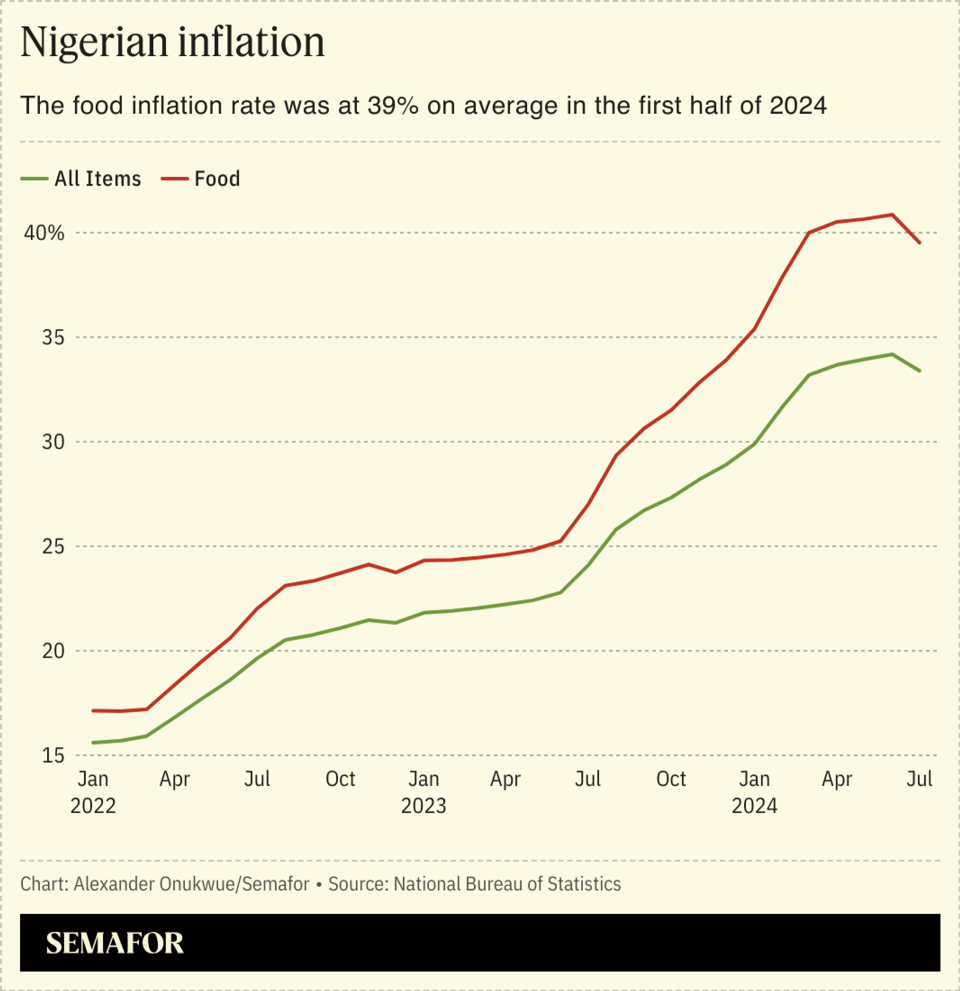

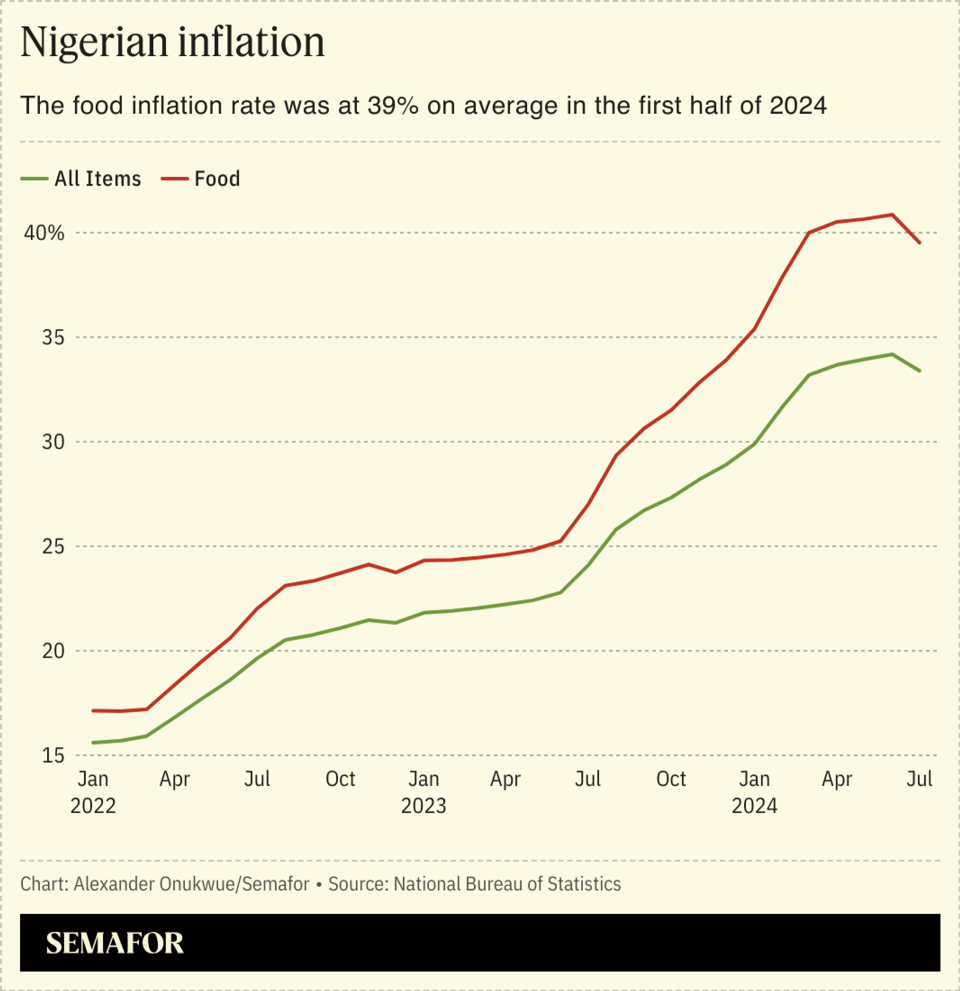

Higher prices threaten to undercut recent gains made towards curbing skyrocketing inflation. Fuel lines that began to appear at pump stations a week ago in Nigeria’s capital Abuja have grown in recent days.

Clusters of black market sellers wielding jerry cans and hoses dot the city — even by the headquarters of the state oil company NNPC — offering quicker service at higher prices to desperate buyers. In Lagos, roads have become emptier with fewer cars on major routes.

The price hike has led to a fresh surge in the cost of food. Increased fuel prices raise the cost of producing and transporting food across the country, which has been passed on to consumers. “I’m barely surviving these days,” Lawrence Chukwuma, a civil servant in Abuja who spent over two hours in a fuel line on Wednesday morning, told Semafor Africa. “I’m now rationing meals to once a day.”

“This government doesn’t want the masses to breathe,” said Jimoh Abefe, 58, a father of six who has driven taxis for more than 30 years in Abuja. He started when Nigerian petrol cost less than half a naira in the late 1980s but is now considering a shift to another trade as the price edges closer to 1,000 naira (63 cents) per liter.

Nigeria’s deputy oil minister Heineken Lokpobiri said on Thursday that “there is sufficient fuel supply in the country, and by the weekend, we expect products to be available nationwide.” President Bola Tinubu, who also doubles as the oil minister, is in Beijing for the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation summit.

Know More

NNPC has blamed the scarcity on its debt to Nigeria’s suppliers of imported refined fuel. “This financial strain has placed considerable pressure on the company and poses a threat to the sustainability of fuel supply,” it said on Sunday. The company previously denied reports that it owed importers $6 billion.

Billionaire industrialist Aliko Dangote said his 650,000-barrel-a-day refinery in Lagos is finally ready to ship petrol to Nigerian consumers, and that it would solve the ongoing problem. NNPC will be its sole buyer and government ministers will determine prices, he said. His comments follow a protracted row with Nigerian authorities.

But Bloomberg, citing sources, on Thursday reported that Nigeria is considering allowing Dangote’s refinery to set the price of the gasoline it sells.

Alexander’s view

Visceral anger and despair were the most common feelings I noted from speaking to people on fuel lines and elsewhere this week. The physical and emotional squeeze in the 16 months since Tinubu became Nigeria’s president have felt like shock therapy — albeit without improvements to justify the pain.

Many feel unsettled because the government appears to be erratic, or at least uncertain in its approach to achieving desired outcomes.

Tinubu proclaimed a decades-old petrol subsidy scheme gone in his inaugural address last year, following years of recommendations by the International Monetary Fund. But the subsidy has returned with a $3.4 billion bill for this year, 50% higher than it cost in 2023. Meanwhile food and transportation prices have in many cases tripled.

“The subsidy program is out of control,” Adedayo Ademuwagun, a Lagos-based analyst at political risk consultancy Songhai Advisory, told me. The “chaos at the moment” is because the government continues to lack clarity about the program, he said.

He foresees “continued turbulence in the next year” over petrol supply, and expects Nigeria’s high inflation rate — which slowed marginally in July — to shoot up again as small businesses and companies begin reviewing prices.

Nigeria has seen a flurry of multinationals like drinks maker Diageo and personal care giant Procter & Gamble exit or scale down operations in the past year. Others could be re-evaluating their positions, if there is no end in sight to the shocks to consumer’s spending power.

I had a particularly telling conversation with a gray-haired former government accountant who only gave his first name, Steven. He was in the third hour of a wait outside a pump station opposite NNPC’s headquarters.

Steven told me his Honda SUV was a retirement gift in 2014 but it had become a burden. “My 50,000 naira monthly pension cannot fuel half of my car’s tank,” he said. Steven told me he had only one wish: that he could help his children leave Nigeria.