Fungi are fascinating lifeforms that defy conventional notions of animal intelligence. They don’t have brains, yet display clear signs of decision making and communication. But just how complex are these organisms and what can they tell us about other forms of awareness? To begin investigating these mysteries, researchers at Japan’s Tohoku University and Nagaoka College conducted a straightforward test to observe the decision-making prowess of a cord-forming fungus known as Phanerochaete velutina. According to the team’s study published in Fungal Ecology, their findings indicate fungi can “recognize” different spatial arrangements of wood and adapt accordingly to make the most of their world.

Although many people only recognize fungi by their aboveground mushrooms, those formations are just the outermost display of an often vast network of underground threads called mycelium. These interconnected webs are capable of relaying environmental information throughout an entire system that can stretch for miles. But mycelium’s growth doesn’t necessarily extend in every direction at random—it appears to be a calculated effort.

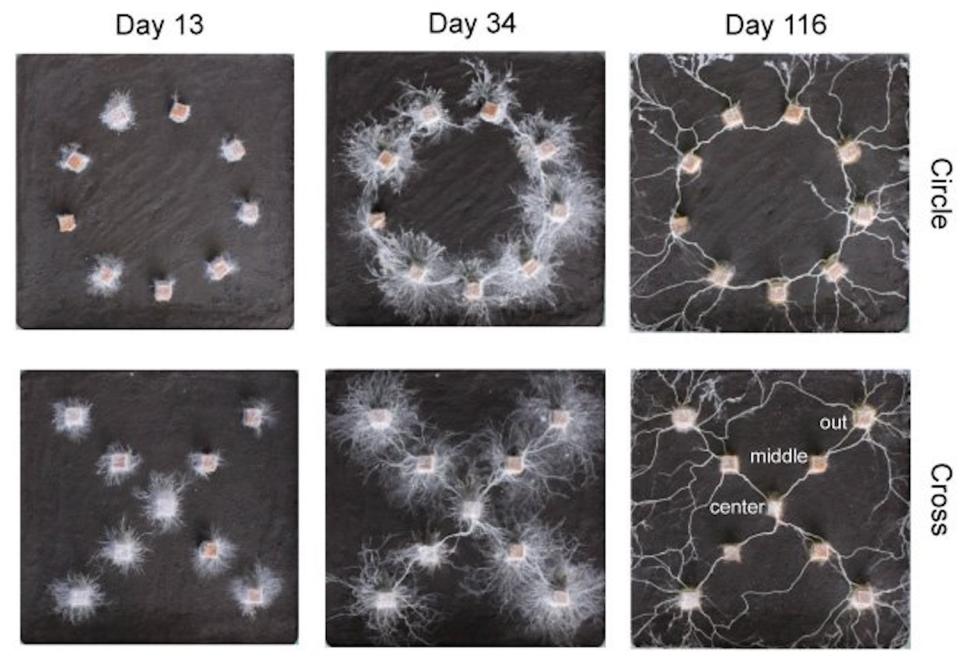

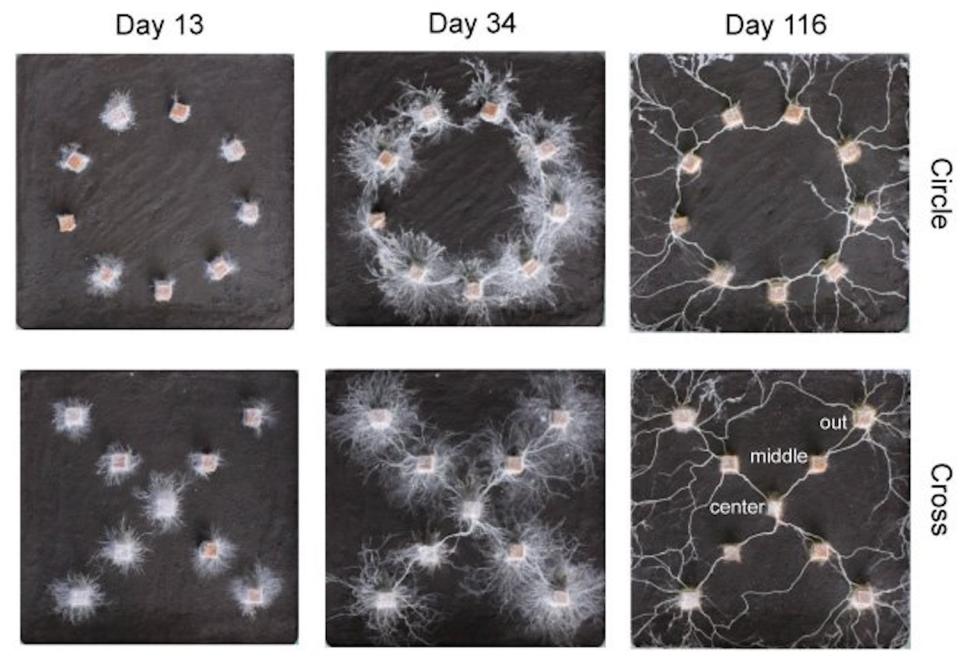

To demonstrate this ability, researchers set up two 24-cm-wide (9.44-in-wide) square dirt environments and soaked decaying wood blocks for 42 days in a solution containing P. velutina spores. They then placed the blocks in either a circular or cross-shaped arrangement inside the box, and let the fungi go about its business for 116 days. If the P. velutina grew at random, then it would indicate a lack of basal cognition decision-making—but that’s not what happened at all.

At first, the mycelium grew outward around each block for 13 days without connecting to each other. About a month later, however, both arrangements displayed extremely tangled fungi webs stretching between every wood sample. But then, something striking occurred—by day 116, each fungal network had organized itself along much more deliberate, clearly defined pathways. In the circle setting, P. velutina displayed uniform connectivity growing outward, but barely grew into the ring’s interior. Meanwhile, the cross fungi extended much further from its four outermost blocks.

[Related: This robot is being controlled by a King oyster mushroom.]

Researchers theorized that, in the circular environment, the mycelial network determined there was little benefit to expend excess energy into a region it already occupied. In the case of the cross scenario, the team thinks that the four exterior post’s growth areas served as “outposts” for foraging missions. Taken together, the two tests strongly suggest networks of brainless organisms communicated between each other through the mycelial networks to grow according to the environmental situations.

“You’d be surprised at just how much fungi are capable of. They have memories, they learn, and they can make decisions,” Yu Fukasawa, a study co-author at Tohoku University, said in the paper’s announcement on October 8th. “Quite frankly, the differences in how they solve problems compared to humans is mind-blowing.”

While much remains to be understood about these often overlooked organisms, researchers believe continued experimentation and analysis may lead to a better understanding of the broader evolutionary history of consciousness, and even chart a path towards advanced bio-based computers.