Two families in East Germany, longing for freedom, built their own hot air balloon out of masses of taffeta, bought secretly in preparations that took more than a year.

They planned to flee and cross into West Germany in a daring plan put into action in September 1979.

They set out in their craft on a moonlit September night – after a failed attempt when they ran out of gas in the air and crashed into the bushes below.

However, they managed to reach the West in their second try, making it out of the country in a highly dramatic feat just before the East German police caught up with them.

The two families were dicing with death, as guards protecting the border in East Germany, then part of the Eastern Bloc, were ordered to use lethal force to prevent people defecting to the West.

The inner German border and the Berlin Wall were heavily fortified with watchtowers, land mines, armed soldiers and other measures to prevent illegal crossings.

“We didn’t know anything about ballooning,” says Günter Wetzel, 69, from one of the two families who managed to flee in their homemade balloon, who researched at length after a television programme provided inspiration.

When asked whether his dreams have been fulfilled in his new home, he replies soberly, “What do you mean by dreams?” Wetzel, who retrained as a car mechanic, was sure it would all work out.

His story was later made into several films. His character was played by US star Beau Bridges in the Disney film “Nightcrossing” and by David Kross in a German movie called “Balloon” (2018).

Sadly the films did not make him rich, however. “We were naive,” he says, looking back.

Exploring the former death strip

A sign located on what used to be East Germany’s infamous death strip now tells visitors about the balloon flight, known worldwide for its boldness.

Following World War II, Germany was divided for decades, separated by a lengthy border that can now be walked by hikers.

Where the death strip ran along the inner German border, there is now a green belt between the Saxon-Bavarian Vogtland region and the Baltic Sea.

Day trippers are drawn by the combination of forests, moorland, rivers, heathland and low mountain ranges.

Hiking journalist Thorsten Hoyer has covered 1,250 kilometres of the roughly 1,400-kilometre-long green belt in less than a month, but he does not recommend it, saying, “70% of it is over concrete and asphalt.”

Nature is working on reclaiming the terrain, but has not yet managed completely.

The route is modelled on the Kolonnenweg on the east side, where the former East Germany border guards patrolled over perforated slabs.

Today, there is greenery everywhere along the path – though less in the way of tourist infrastructure and in places, there could be better signposting.

So it is better if cyclists and hikers focus on select routes, perhaps in the Franconian Forest where the states of Bavaria and Thuringia meet.

‘Little Berlin’

The river Saale, once a border, flows leisurely along and builds up to a smooth surface near Hirschberg and is lined with trees and bushes, while canoeists rush over a weir. If you cycle along the colonnade path, watch out for the wide depressions in the concrete.

The situation eases on a forest path and the little road to Mödlareuth. Here, Americans used to call the village “Little Berlin.”

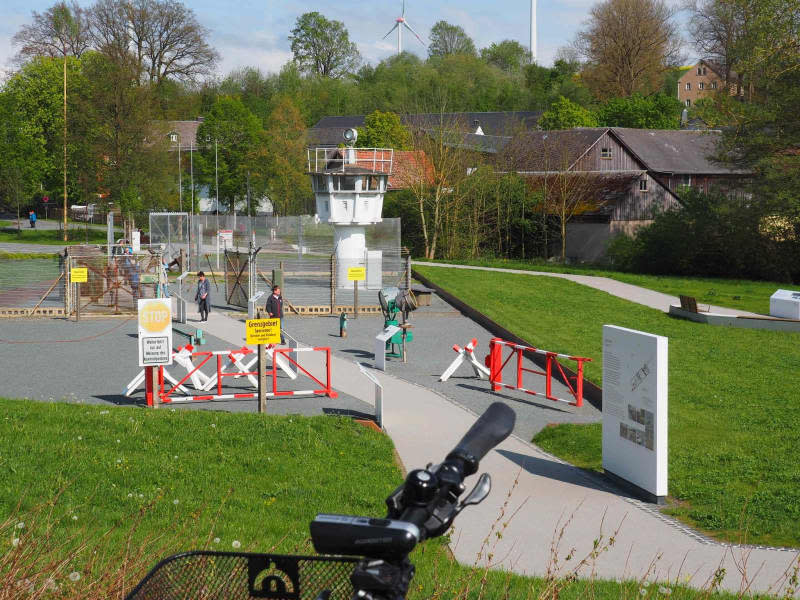

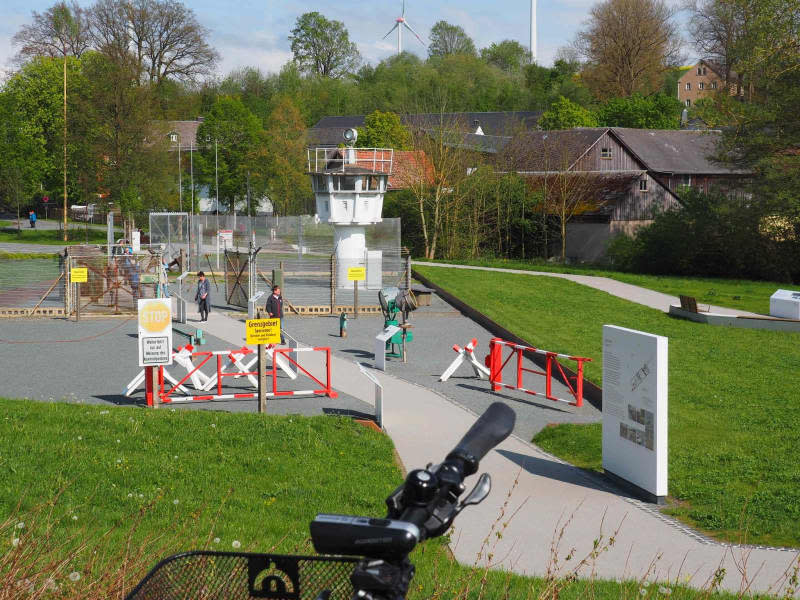

Just like the German capital, Mödlareuth was divided by a wall and you can still visit the German-German Museum which has a memorial to the separation of the country. Visitors can also see a section of the Wall, and watchtowers and barbed wire fences bear witness to the painful division.

Britt Hornig, who is currently wandering through the museum grounds, is deeply moved and agitated. She used to work as a paediatric nurse in East Germany. “There can’t be anything like this again. That was my childhood, my youth. It was absolute madness what they did to us.”

“I went to the demonstrations in Leipzig every week and fought for freedom until the Wall came down.”

Otto Oeder, a former border policeman and now 79 years old, also recalls the division. “I thought the world ended there,” he says, describing his deployment on the Bavarian side of the Iron Curtain.

He wrote and published his book about those divided years, recalling refugees who made it through. “At our police station, we first dressed them in dry clothes, donated by us, not paid for by the state.”

He also set up a regular meeting point in a pub for people who had crossed the border and could share their anecdotes. Anyone loyal to the East German regime was unwelcome.

Hiking through the past

Frankenwald-Steigla is the name of a network of circular hiking trails in the Franconian Forest, three of which illustrate the German-German past.

The Wetzsteinmacher trail, 5.3 kilometres long and starting below Lauenstein Castle, leads up to the Thüringer Warte. It is a viewing tower on the summit of the Ratzenberg and provides a fantastic vantage point to survey the area. Climb 117 steps and you can take in a view of the forests of the Thuringian-Franconian Slate Mountains.

Other climbs include the challenging Grenzer-Weg trail – 16.8 kilometres from Carlsgrün – and the moderate, recently inaugurated 10-kilometre Grünes Band trail, which starts in Mitwitz.

Along the way, a stream babbles and cuckoo calls echo through the forest. You can hear birdsong, while dewdrops sparkle like pearls on blades of grass. Dragonflies dance in the sun and it is so peaceful that you cannot imagine anything ever happened here.